The Unjust Judge and the Persistent Widow: The Curious Case of the Brett Kavanaugh Nomination

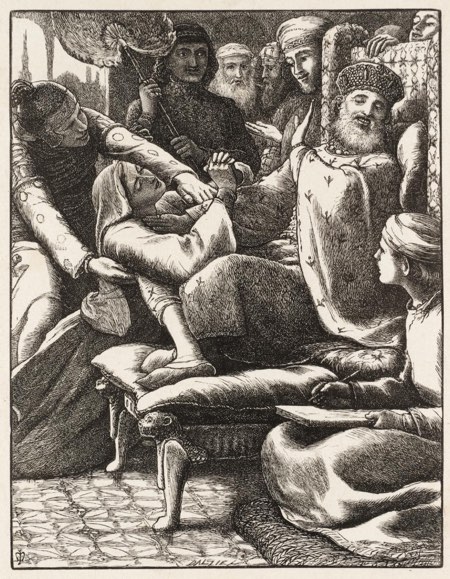

Jesus tells the story in the Gospel of Luke about a widow who goes to see “a judge who neither feared God nor had respect for people” (18:2). She asks the judge to grant her justice against her opponent. We don’t get any further information about the opponent or the nature of the injustice from which the widow seeks redress—the text doesn’t provide any details—but the story suggests that her grievances are severe enough that the widow is motivated to keep coming to the judge in search of relief.

What we do know is that every time the woman asks for justice, the judge refuses her. Finally, however, the judge relents—not, apparently, because he’s come to his senses about the truth of the woman’s claim, but because he’s tired of being worn out by this woman’s ceaseless requests for justice.

The story concludes by suggesting that—unlike the unjust judge—God doesn’t need to be badgered into dispensing justice for those who cry out “day and night.”

Now, in Luke’s hands, this parable becomes an exhortation to “pray always and not to lose heart” (18:1). Traditionally, the interpreters of this passage have continued on this trajectory of textual spiritualization, rendering the few details of the parable as extraneous and unnecessary for understanding the spiritual intention of this story.

So, she’s a widow, big deal. It could just as easily have been a man seeking justice. The point is the persistence in asking.

So, it’s a judge, who cares? It could have been a farmer or a merchant who happened also to be callous. The point is that an imperfect human being refused to respond to the woman’s cries, which is obviously unlike how God would handle it.

In other words, Jesus pulls a couple of stock characters out of the narrative hat, puts them together in a situation that allows him to show how generous and helpful God is to those who keep asking.

What this traditional spiritual interpretation of the persistent widow and the unjust judge fails to take into account is that Jesus doesn’t use just any characters; he uses a widow and a judge to tell this story—not a man and a merchant. This acknowledgment of the details is important because widows and unjust judges were people everyone knew. And this kind of justice-seeking by the powerless was an occurrence everyone could immediately understand.

Widows in the ancient Near East were among the most vulnerable members of society, obvious and frequent targets of exploitation by those in power. The fact that Jesus used the character in the story of a powerless widow on the verge of destitution and exploitation isn’t a throw-away detail; it’s central to the point he wants to make.

Moreover, this unsympathetic judge isn’t just an obnoxious neighbor who refuses to clean up after his 200 lb. Mastiff, thus causing the woman to experience paroxysms of fury. This is the man in the community who has power over people’s lives and futures. That the judge feels no particular moral obligation toward the woman is, in the mind Jesus’ Jewish listeners, an affront to the demands of Torah. An unjust judge is like a physician who actively and with knowledge makes people sick.

Setting aside Luke’s focus on prayer, in this parable Jesus takes aim at a state of affairs in which the powerless find themselves repeatedly at the mercy of those who have power over them. Jesus is, in other words, indicting a system in which widows can’t assume they’ll receive justice. In order to find it, they have to make spectacles of themselves, embarrassing and shaming the powerful who are supposed not only to know better, but to be better.

All of this got me to thinking about the sordid Senate hearing surrounding Supreme Court nominee, Judge Brett Kavanaugh. Judge Kavanaugh is accused of sexual assault by multiple women at this point. These women have appealed to the president and to the eleven Republican men on the Senate Judiciary Committee for a little justice, for an investigation of the charges they’ve made. And repeatedly, the powerful men had denied Judge Kavanaugh’s accusers, making reference to the committee’s diffidence about pursuing the allegations at this late hour—because, really, hasn’t he already gone through enough? (The majority has since relented, not, generally speaking, out a sense of duty, but because they don’t have sufficient numbers to press forward to a vote.)

Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, in one of the most courageous acts of civic minded honesty I have ever witnessed, went willingly before the nation to plead her case for justice—only to be dismissed by some GOP senators as an unwitting dupe, a victim of a conspiracy she apparently didn’t have the intellectual capacity to understand. She was patronized, abused yet again by men with power over her, who shamelessly took advantage of her vulnerability in coming forward with such a humiliating and traumatizing story—all the while intending to ignore that story.

These men listened to a story from Judge Kavanaugh’s past about a vulnerable woman who cried out to him for justice—the first time (literally cried out) locked in an upstairs bedroom with the stereo blasting—only to have him ignore her pleas.

How is it that after all these years so many who claim to follow Jesus still find themselves propping up a system in which the vulnerable have to cry out to powerful, self-protecting men for a little justice?

How can we who strive to live like the one who befriended forgotten and silenced women remain silent ourselves in the face of unjust judges, who—because of their willingness to ignore those who “cry out to God day and night” for justice—have shown themselves to be those who “neither fear God nor have respect for people?”

How do we look past a cozy patriarchal arrangement in which violent men receive the benefit of the doubt, while women on the margins have to swallow their dignity to catch the attention of those who sit in judgment on whether women’s stories are worth hearing?

I don’t have all the answers to those questions. But to my fellow co-religionists I would say: maybe looking to Jesus might be a good place to start.